Tell Them and They Will Believe—and Buy: The Power of Advertising to Persuade

Advertising in America really took off with the advent of print media—in particular, newspapers and magazines. These print media provided businesses and services with a platform on which to entice the public to buy into what they had to offer while, at the same time, it also provided the media themselves with the capital they needed to exist. As the 19th and early 20th century progressed, the business of advertising became more specialized and professionalized, and by the time the recording industry was finding its economic footing around the year 1900, most recording businesses either had in-house advertising staffs or hired independent advertising companies (the first advertising company opened in 1841; there were 21 advertising agencies in New York City alone in 1861 [Gartrell and Pritcher, n.d.], a full fifteen years before Edison invented sound capture and about 30 years before the record industry started to take shape) to promote their products to, and persuade, the general public through ads placed in newspapers and magazines, the only media of the day with the kind of reach that developing industries of the day (automobile, furniture, clothing, tobacco products, alcohol beverages, medicine, and appliance manufacturers, for example) needed to survive. In the mid-1920s, a new advertising platform started to emerge—radio—that would gradually challenge the hegemony of print media as the primary platform for advertising. Radio did not replace print media as an advertising platform but did offer businesses an additional platform through which to reach potential consumers. The same can be said for television beginning in the 1950s. It wasn’t until the very end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century that, with the advent of digital communication networks and the introduction of personal computers, smartphones, and the internet, that print media finally met its match. As advertisers and companies became increasingly facile with the digital environment and figured out ways to individualize their enticements to buy to individual consumer’s digital devices, the print media themselves have had to figure out (and continue in their attempts to figure out) how to survive in the present-day reality of a smartphone- and internet-centric world.

Advertisements begin to appear in urban newspapers in the 1850s and national monthly magazines in the 1860s. At first only in black-and-white, color ads began to appear by the mid-1890s. Many (but not all) of the advertisements included in the Grinnell College collection are in color, and many take up a full page or are in the two-page-spread format. While ads for spring-motor driven, fully acoustic phonographs are the primary focus of the collection, ads heralding the availability of radios, either on their own or as a component alongside an electrified phonograph, are also included, along with a few ads for sound capture and playback technologies that developed around the middle of the 20th century.

We present below several themes that were drawn on by the recording industry and advertising agencies in their advertising. For each theme, one or a few ads will be presented as illustrations of them.

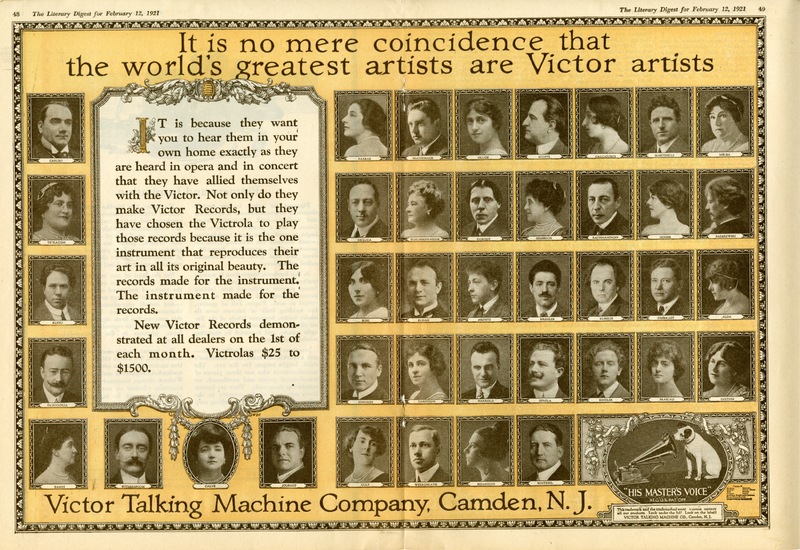

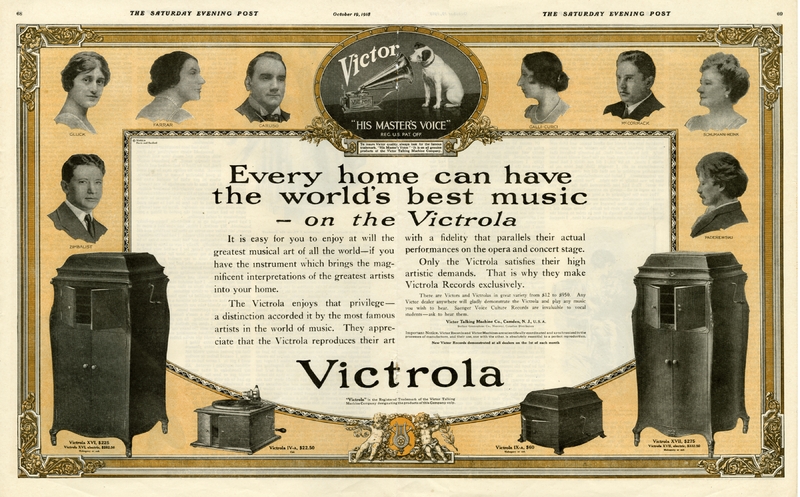

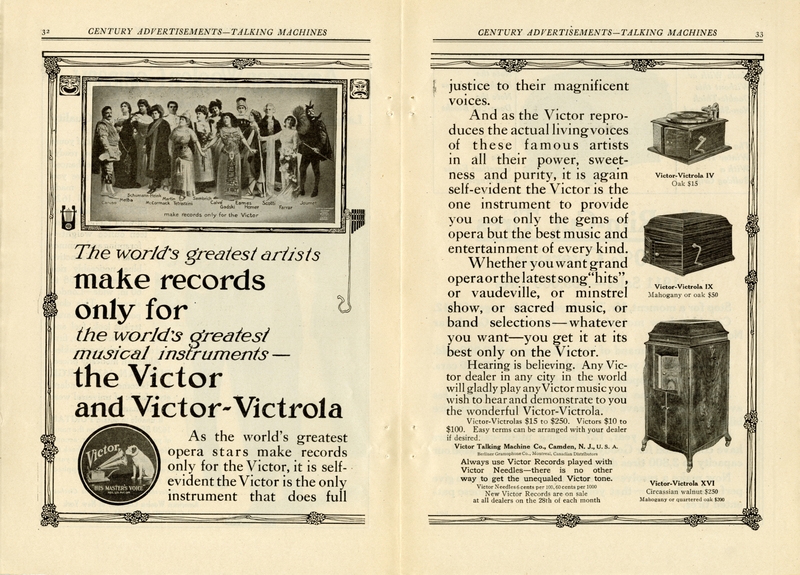

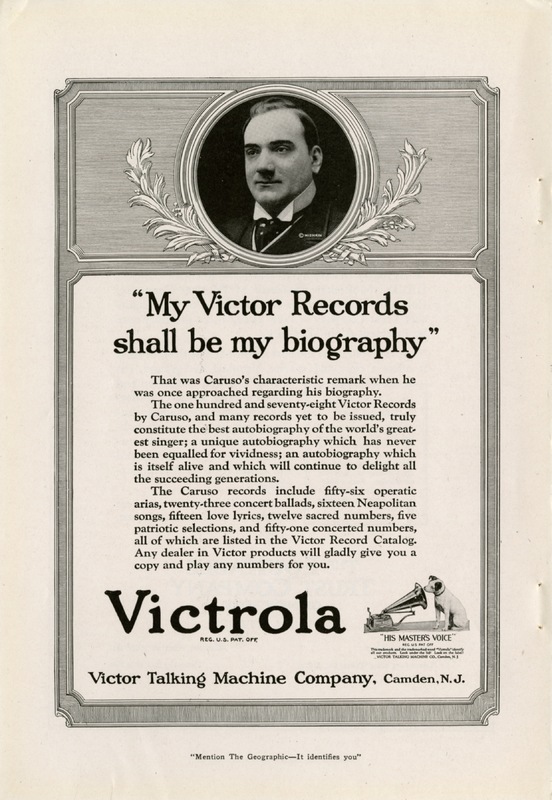

Celebrity Endorsement: Boasting about a company’s products was often validated in ads through celebrity endorsement. The celebrities are usually the musicians heard on the recordings but, as the second example illustrates, other celebrities can be enlisted.

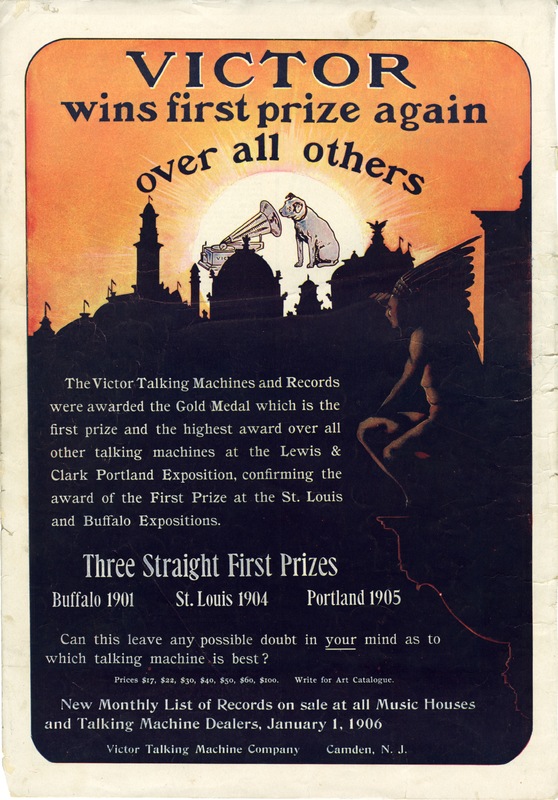

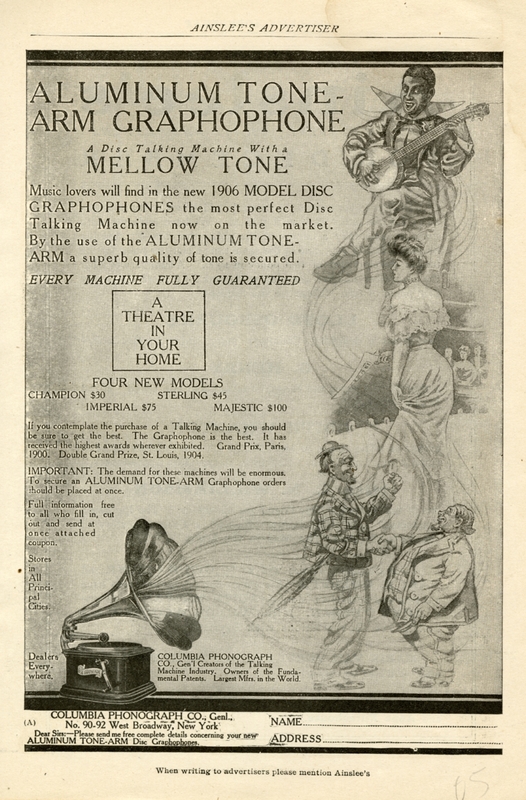

Award Winning: Around the turn of the 20th century, recording companies sought out awards for their record players and phonograms at World Expositions. Such endorsements were utilized to the advantage of the “winning” recording companies even though who was doing the judging and on what criteria they were basing their awards are seldom if ever mentioned.

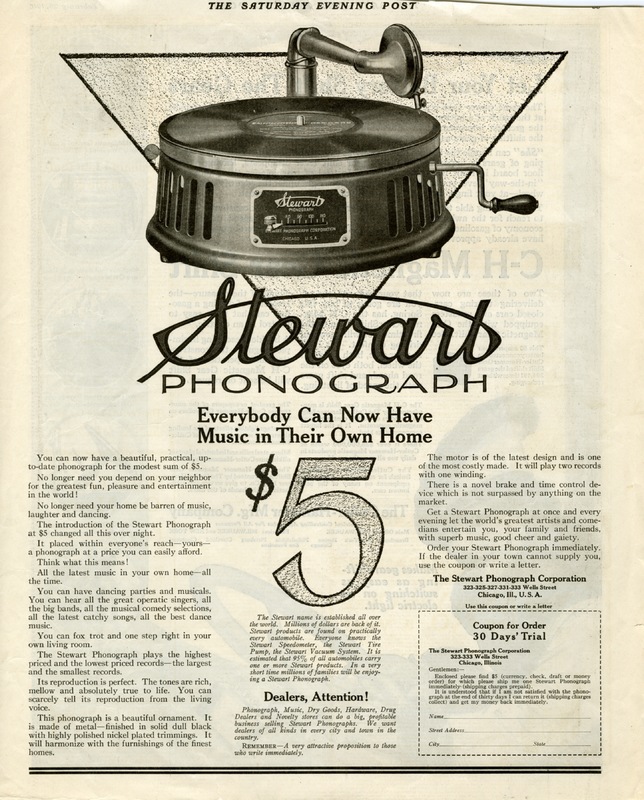

A Phonograph for Every Stratum of Society: Recording companies produced a diverse array of phonographs, each targeting a market of consumers who could afford to purchase a phonograph whose price tag reflected their financial means. Remember when looking at the prices of these advertised phonographs that they ARE NOT in present-day dollars.

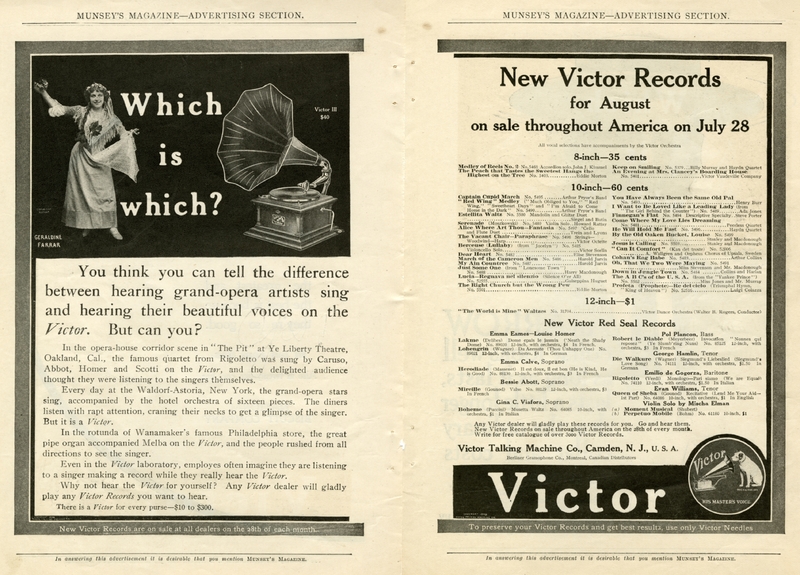

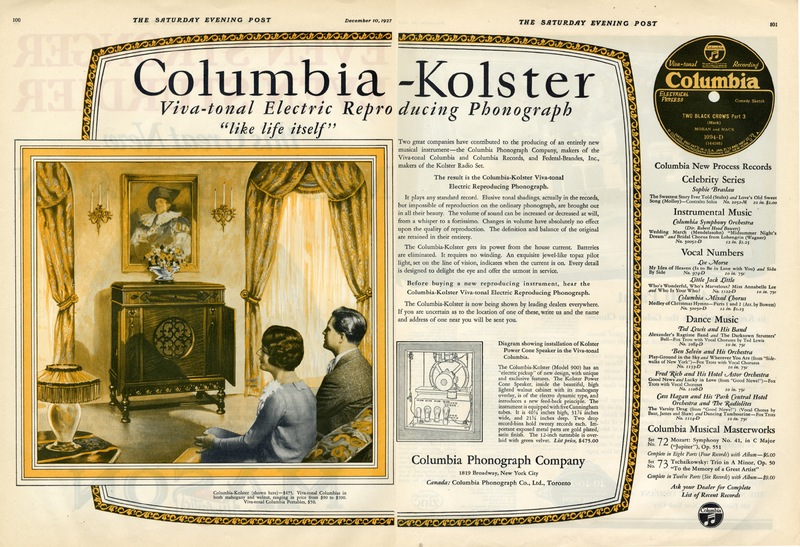

Breadth of Repertoire: Recording companies would often boast about the breadth of musical repertoire and styles that they made available, as the Victor company does in the final paragraph of this ad. “We produce something for everyone” is the pitch they were making to the general public.

Life-like Sound of Recordings: Recording companies often told their potential customers in their ads that there was no qualitative difference between experiencing a great performer’s voice (or the instrument they were performing) live and on a phonogram. This was, of course, not true, especially in the early decades of sound capture. There must have been a belief amongst creators of ads that if you tell the consumer public something consistently and over a period of time, they (the consumers) will come to believe it. [See also the ad about Edison’s “tone tests” in the Special Topics essay “Is the Phonograph a Musical Instrument” elsewhere on this website.]

Education and Edification: Many record company advertisements were directed to women, who were tasked with bringing up well educated and edified children. Having and playing in the home for the benefit of one’s children, recordings of “the best” music was pitched in ads—very consciously to mothers--as a means of accomplishing these ends.

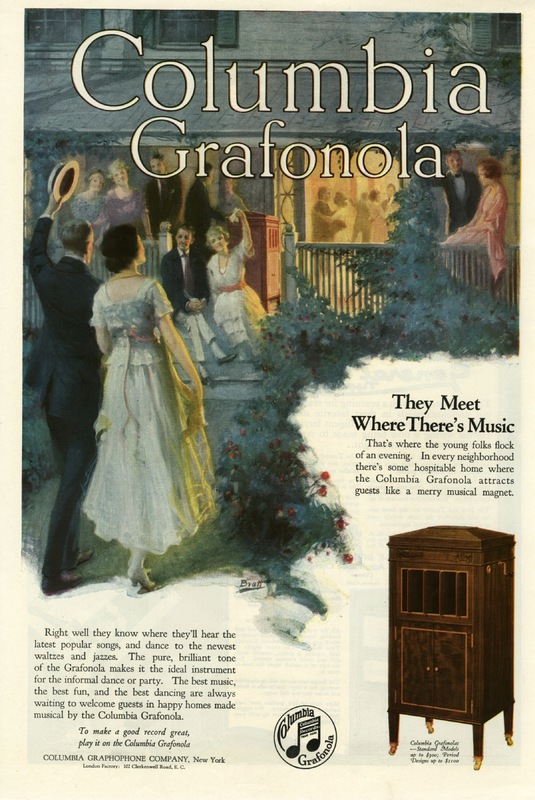

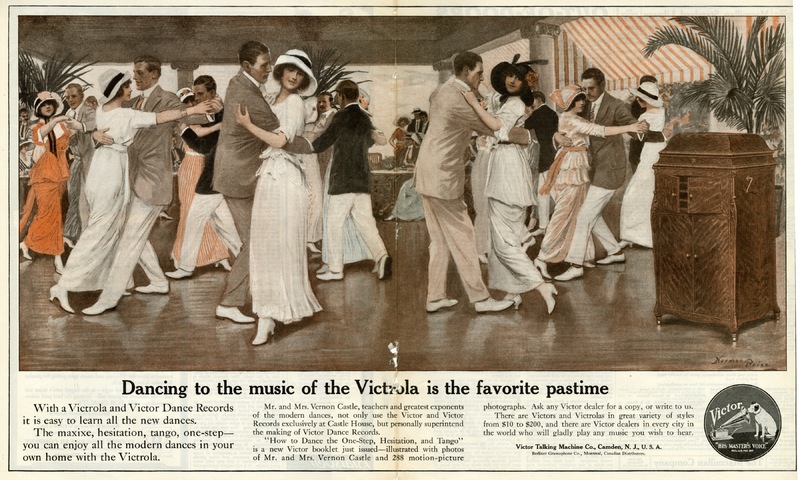

Dance at Home: In the early years of the 20th century, dancing at home was much more common than it is today. Yet another selling point for record companies, who boasted about both the robust sound output of their phonographs and the quality of the dance bands who they recorded.

Preservation of Performers’ Artistry for Posterity: One aspect of sound recording is that at least some sense of performers’ artistry is documented when they are recorded. The first of the following two ads drives this point home by highlighting a legendary 19th century artist (singer Jenny Lind) and the fact that she was active at a time when there was no sound capture (and, therefore, her voice did not live on to be enjoyed by later generations). The second ad focuses on the operatic tenor Enrico Caruso, who had perhaps the most recorded voice in the early decades of sound capture (and his voice will live on for years after he has passed, which it has [there are many re-releases of his original records still available today on formats that didn’t even exist when he was alive.])

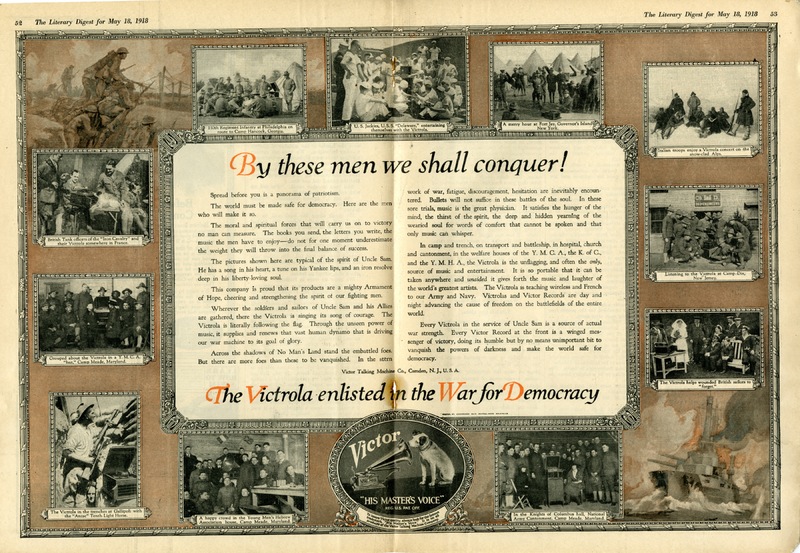

Recorded Music in the (WWI) War Effort: In addition to producing phonograph models during WWI for the various branches of the military, recording companies attempted to display how their products could support troop moral on the battle front.

Portability of Listening to Music: The 1920s was the decade when the recording industry realized that a new market of consumers could be tapped with suitcase-like portable phonographs. Both industrial giants, like Victor (see the ad below), and numerous off-brand phonograph manufacturers such as the anonymous company that produced the Roxy phonograph in the Grinnell Collection, partook in this venture.

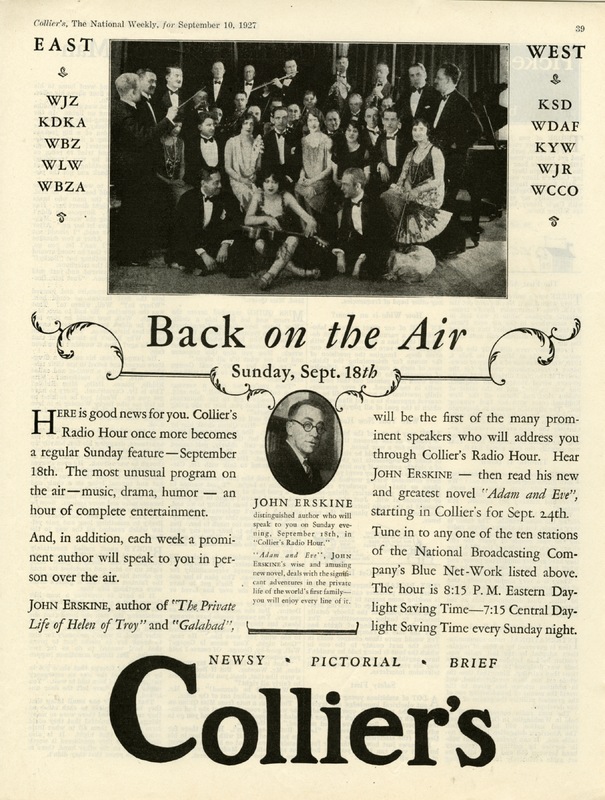

Radio’s Introduction: Around the middle of the 1920s, radios began to be marketed. In the first ad that follows, many of the rhetorical devices used in the selling of phonographs can also be found in radio ads. In the second ad, one can sense the difference in programing content that could be delivered through the radio and that couldn’t be found on a record.

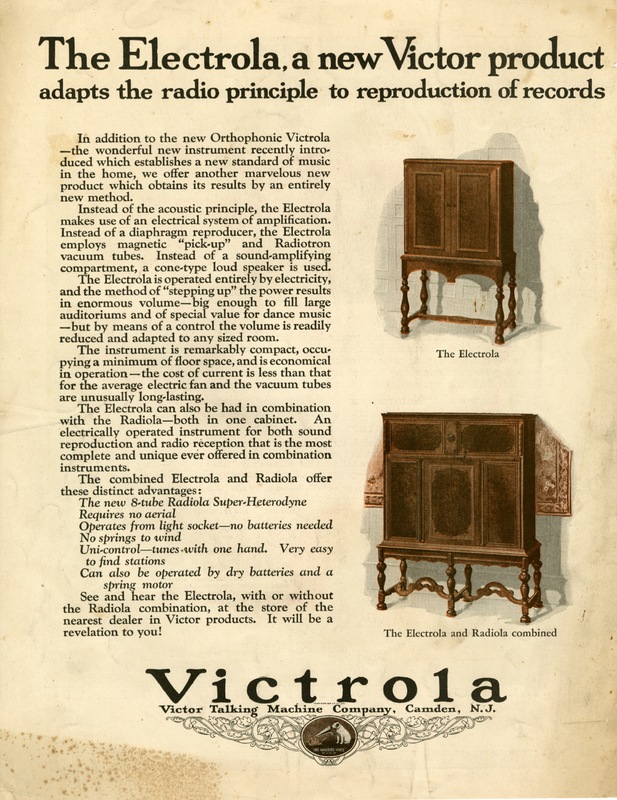

Technological Innovation: In the early years of the phonograph industry, almost any new idea incorporated into a company’s products would be amplified in its ads (the first ad below; one of the models mentioned in this ad is found in the Grinnell College collection—The Sterling). Really dramatic engineering innovations—mostly to do with electrification of phonographs and the introduction of radio—started to take place in the 1920s. The second and third ads that follow show how industry giants such as Victor and Columbia quickly got on board this wave of innovation.

Resources

Gartrell, Ellen, and Lynn Pritcher. Research guide: “Emergence of Advertising in America: 1850-1920,“ Duke University Libraries website, accessed Jan. 24, 2026: https://guides.library.duke.edu/c.php?g=494860&p=3386128